This is a written version of a speech made several weeks ago by the johnson banks Creative Director, Michael Johnson for the Typographic Circle in London.

My first design decade was spent learning the basic grammar of my chosen trade, and the differences between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ design. My second design decade was spent working out how to run a business.

But seeds of doubt regarding the third were sown early. I started to question that idea of ‘good’ design, and when good might actually be bad. I’d become adept at ‘beautiful’ design, but all that beauty sold was more paper, or watches, or suchlike.

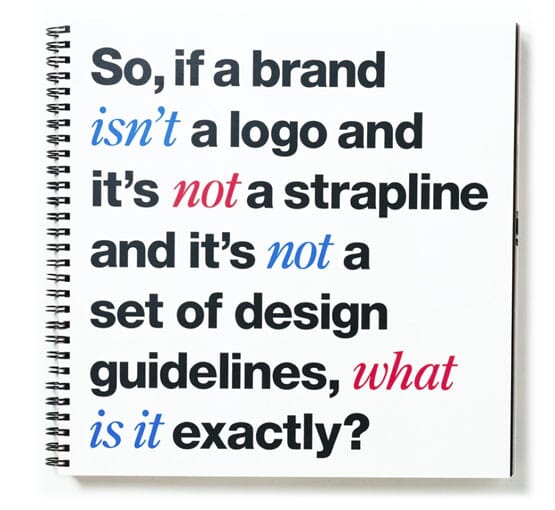

I started to learn and develop branding theory as a hired gun for the likes of BT. But I wasn’t really that interested in BT’s brand. It was fairly profitable, so happy bank account, you might say. But, unhappy soul.

Then clients that on paper were exciting and interesting, such as PolyGram, seemed unhealthily dependent on the release of the new U2 album for their own survival. I began to wonder if I too really wanted to be dependent on Bono for the fortunes of johnson banks.

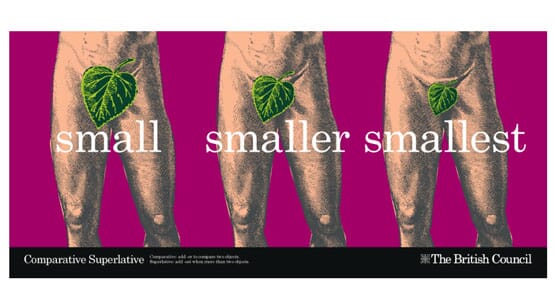

Starting to dig deeper At the turn of the century, we started to do projects that hinted at something deeper, something more useful, such as these classroom cards for the British Council.

With a touch of humour, a lot of research, and some lateral thinking we’d developed a way of explaining the nuances of learning English, and some of its idiosyncrasies. Students liked them, teachers used them. Thousands of people across the world engaged with comparative superlatives in new way. Projects like this made me ask questions: how could we do more things that were actually useful, and actually meaningful?

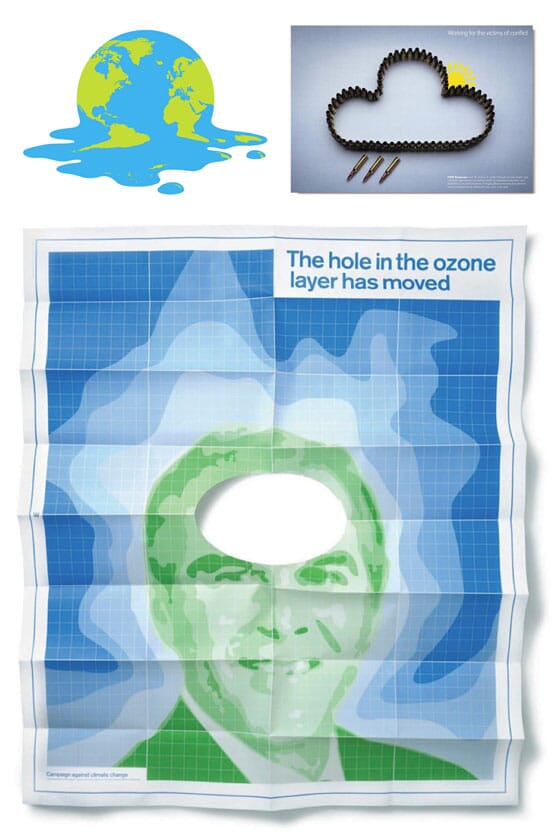

The next phase was to accept virtually any commission that came our way that had a social mission. A plethora of posters followed on multiple causes, from global warming and ozone layers to US Presidents and conflict victims.

These looked great on the wall. They appeared in exhibitions, even won the odd award. But, looking back through honesty-tinted spectacles, they didn’t achieve what I’d hoped. Like the more recent furore over designers reacting to Fukushima with endless posters featuring obligatory red circles, was this the best that graphic designers could do? Did the world really need another hand-printed, hand-held, limited edition poster? OK, some of them raised tens of thousands, but what happens if you want to do work that raises tens of millions?

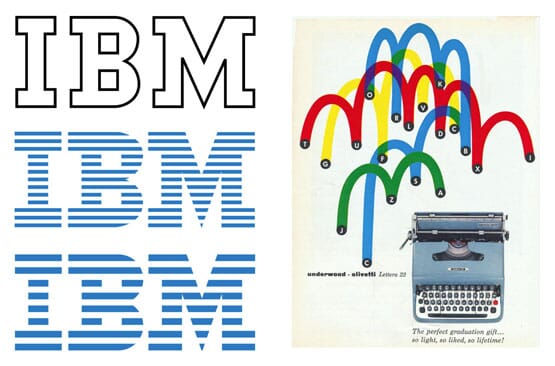

Searching for precedent In the graphic design business the search for heroes is easy, but the search for ‘good’ mentors is much harder. My post war favourites worked for the likes of IBM and Olivetti. Then two generations of designers suggested to us that designing record sleeves should be our career zenith.

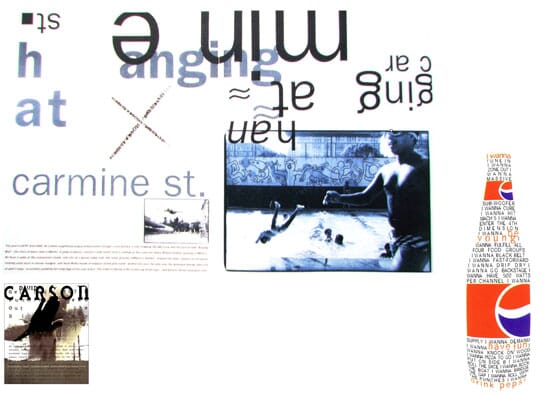

Celebrated and skilful designers started off breaking all the rules then ended up designing ads for Pepsi, or type for Nike. But this thought nagged at me - shouldn’t we be aiming higher than flogging fizzy drinks and trainers?

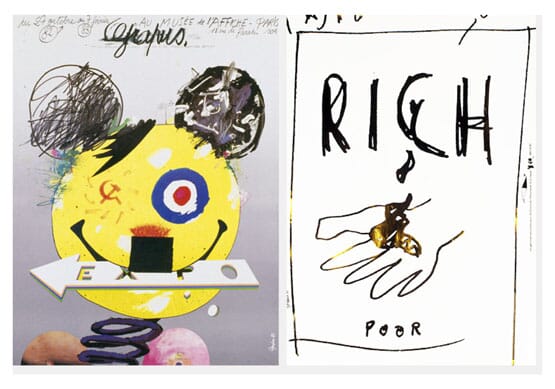

The designers we traditionally turned to for precedent in ‘design for good’ used ‘agit’ as their graphic voice. Ideal if you want to agitate, but not everyone wants to argue, (well, not constantly).

Even written precedent, such as the re-purposed First Things First Manifesto, wasn’t especially helpful. The demand to work on social and cultural crises that ‘demand our attention’ was admirable. Yet only a paragraph away ‘designers who devote their efforts primarily to advertising, marketing and brand development’ were chastised. If you spend most of your time doing large identity projects, you’re interfacing with all of these on a daily basis. If you want to affect serious change, you need to embrace 21st century communications, not put your head in designer sand and hope it goes away.

In the meantime, mainstream designers still seem to be unhealthy obsessed with winning awards, or producing nice little self-promotional projects. Luckily you can now indeed win specific awards for exactly that (proof perhaps that left to its own devices design becomes increasingly self referential).

To do serious work, design needs to be taken seriously For Shelter we were determined to supply a grown-up, rigorous solution (although this undoubtedly cost us thousands to deliver). But it helped make the next step crystal clear: to gain serious traction, we needed to raise ourselves up from the occasional poster and one-off logo and find a voice in the boardroom.

This meant long periods of research and analysis as we started to work with Save the Children in the UK, writing ‘boiler-plate’ statements that ran through the organisation’s work, speeches and advocacy for years.

Sometimes we had to stop designing and start thinking: our rebrand of Anthony Nolan started with an erroneous brief that they were still an organisation concerned with Leukaemia. Only later did it become clear that ‘matching’ was a far better purpose for a bone marrow registry that could save lives.

The desire to make a difference can straddle sectors, such as re-igniting school children’s interest in science as a topic and eventual career, or re-framing a nation’s awareness of a misunderstood condition like Cystic Fibrosis. And the results can back this up: in the UK Save the Children more than doubled their income in 5 years; Anthony Nolan’s funds increased 46% just one year after relaunch; the DEC’s new messaging and visuals have helped raise £16 million and counting for a very tricky appeal for the Syrian Crisis and King's College have raised a staggering £450 million for their development campaign.

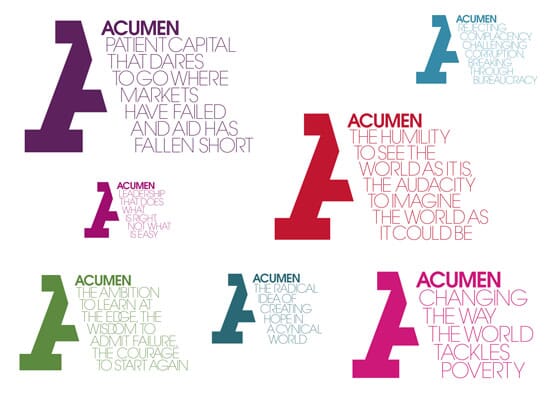

Proof and impact The project that has proved the tipping point for us in design for ‘good’ has been our work for Acumen. After a decade spent working with aid NGOs, Acumen’s determination and track record in achieving measurable impact by supporting innovation in developing nations has been refreshing.

Their success stories are legion. One of their most famous began in 2005 with Ziqitza Health Care Limited who were trying to start a high quality ambulance service in Mumbai. Prior to ZHL, to get to hospital people were using auto rickshaws, private cars or van 'ambulances' with no medical equipment or trained technicians. More often than not, these ambulances were functioning as hearses - 9 out of 10 were transporting dead bodies.

In 2007, Acumen invested $1.6million to operate 10 ZHL ambulances. Their operations have state-of-the-art 24/7 call centres with ambulance tracking systems, one single number to call, and equip ambulances with personnel trained in life support. They have served over 1 million people since 2005, have 870 ambulances in 5 states across India, with an ambulance usually arriving within 15 minutes after a call.

But as market leader, they’d been followed by hundreds of competitors into this new sector, keen to offer investment with a social conscience. We spent much of 2012 co-authoring a manifesto that confirmed their position as thought leaders, then delivering an identity that embeds this thinking into their visual approach.

Forget about lunch Whilst there are many great and rewarding sides to working the not-for-profit, education and cultural sectors, there are other realities. This is not the kind work that wins design awards. These are sectors where lunch is more likely to be eaten by someone else, in front of you as you present, not a three-hour stretch in a Soho haunt. Democracy can demand endless, iterative stages of development - we stopped counting the drafts of Acumen’s manifesto after number 22, for example.

And budgets seem to hover at around 70% of blue-chip fees. But that’s beginning to change as organisations realise that a little more money spent can drastically increase funds raised, or visitors attracted.

To raise the fees and professionalism further, we’ll have to become better at proving that design for good works, deserves our support and necessitates a change in client mindset. As activist and fundraiser Dan Palotta points out in this excellent plea for a change of attitude (well worth watching the next time you have a spare 20 minutes)…

‘…we don't like non-profits to use money to incentivise people to produce more in social service. We have a visceral reaction to the idea that anyone would make very much money helping other people. Interesting that we don't have a visceral reaction to the notion that people would make a lot of money not helping other people. You know, you want to make 50 million dollars selling violent video games to kids, go for it. We'll put you on the cover of Wired magazine. But you want to make half a million dollars trying to cure kids of malaria,and you're considered a parasite yourself.’

Just think what all that thinking could do Of course this isn’t just about what johnson banks has done or is doing. From Wolff Olins’ groundbreaking schemes for Macmillan and more recently Little Sun, or Hat-Trick’s work for the likes of Action on Hearing Loss, there are great designers out there who can and will work for good causes, and have impressive stats to show the effects of change.

My point is that endlessly churning out self-promotional projects is fine, to a point, but, next time, consider channelling that energy into something more useful. The next generation of designers needs to see that they CAN make a difference, rather than just designing for decoration. It is possible to do ‘great’ design and ‘good’ all of the time, not just some of it. At the end of all this, perhaps design is capable of achieving something genuinely meaningful.