Read a grown-up magazine, or paper, take the tube or just wander down a UK high street and you’re currently subjected to a barrage of banking offers.

This is being driven by two things – the re-emergence of the Trustee Savings Bank (or TSB, for short), and from this week the ability to switch your bank details from one bank to another.

Now, you’d think the advent of increased competition would shake the financial sector out of its branding lethargy, but thus far it’s in short supply. In fact, in our experience, getting imaginative thinking into the banking boardroom is an uphill struggle. At key points, on countless projects, men in blue suits have joined meetings, glanced at the designs and pronounced that ‘these are completely wrong - it must be blue!’ Or ‘the name must be written in capitals!’ (Or if we’re really unlucky, both).

These are usually men, rarely women, paid handsomely to have a view on all things, and see the branding process as something they are expert in as well.

A couple of years ago, we presented a room full of ideas for a major new financial brand. Multiple walls were covered with concepts and approaches, all innovative, interesting and differentiating. The key client arrived late, downed a cafetiere of coffee whilst demolishing a plateful of biscuits then stood up and trashed everything on view.

‘You don’t understand - I want a symbol, next to a piece of type’ he shouted. We pointed out, of course, that this is what everyone in the sector has.

‘Exactly!’

He looked very proud of himself at this breakthrough piece of thinking. All the meetings on brand narrative and perceptive positioning were blown out of the water because the desire for a ‘me-too’, the fear of standing out, the fear of putting one’s head over the parapet, had taken over.

So what keeps happening here? It seems that, however much brand consultants advise new thinking and clarity, this, the most traditional sector of all, doesn’t listen. The innovations, the Zopas and the Kickstarters, all come from elsewhere.

Stand-out services such as More Th>n, always offering more, determined to stand out from the direct insurance pack, are rare. Even though the new name and brand helped it move from 13th in the tables to third in the space of just a few years, it’s still a rare piece of differentiating thinking.

The last decade’s only significant change in this sector has been the advent of money comparison websites, with the same, commodity product differentiated only by meerkats, annoying opera singers or more recently robots.

Meanwhile, in countless surveys bankers come out as reviled as estate agents – with the only bright spot PayPal, seen literally as ‘a friend in a dangerous environment’ (and many of us have had enough angst with our PayPal accounts to query that as well).

So why is it so hard for the finance sector to be seen as a friend? Why is it so hard to be honest, truthful, even ethical? In a recent survey of the brand values of banks, amongst the top ones chosen were those perennial favourites, ‘integrity’, ‘honesty' and ‘respect’, but that message isn’t getting through to the public, at all. Barclays are now promising to ‘help people… …in the right way’ yet are caught in almost weekly scandals of doing things the wrong way (PPI, Libor, you name it).

Despite all this, we haven’t given up completely. We’ve just started work on a new financial brand that will be useful. It will be helpful. It may be, just maybe, a new and important financial innovation for the 21st century. We’re working with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development on their small business advice across 27 countries. We’re working with a foundation in Paris that wants to change the ways we produce and consume, and to be as ethical in our investments as our purchases.

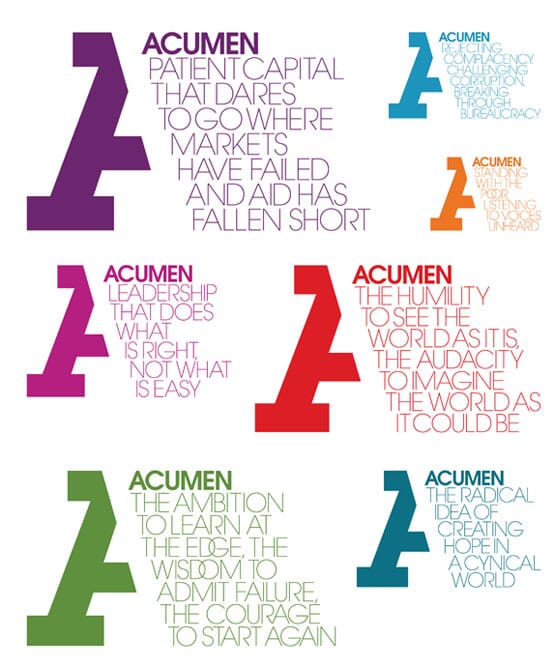

Most importantly, we’ve spent two years working with Acumen in New York, the original impact investor and thought leader in the sector. What glues Acumen together now is a new brand, and a co-written manifesto that ‘demands investing as a means, not an end, requires patience and kindness, resilience and grit - a hard-edged hope’.

Now this is brave. This is honest. And the manifesto appears in everything they do and say across all of their logos, comms, webpages and global chapters, to thousands of supporters and investors.

Back in blighty, all that the revitalized TSB can do is show us a logo much like their old, reset in sans-serif type. All it can tell us on a poster is ‘Hello’. And that it now has 600 odd branches. Pretty much like any other bank then.

But now we can all switch our account within 7 days, rather than the 192 days plus 19 letters in triplicate that preceded it, perhaps the market will be shaken from its collective lethargy and will have to do what other sectors have to do – deliver useful, honest services and consider branding that attracts, not repels.

If the finance sector could only learn a little from the new, social sector, a sector prepared to admit failure, to be honest, to do what’s right, not what’s easy, well just imagine what could happen. (But don't hold your breath).

This piece is adapted from a short talk given recently by Michael Johnson for the Centre for Financial Innovation as part of a round-table discussion with Caitlin Thomas (A new pair of glasses), David Haigh (Brand Finance), and Andrew Marshall (Cognito).