We’ve discovered a series of old pieces in a recent clear-out that seem worthy of another look. Up first - a review of the 2005 Design Museum show dedicated to design legend, Robert Brownjohn.

My guess is that many of this blog’s readers will never have heard of Robert Brownjohn. Yet to those who knew him personally, or know the work, he’s attained a mythical, almost legendary status that might puzzle non-believers. His was a live fast, die (relatively) young tale that left behind many stories of his unhinged lifestyle, but not a vast archive of work.

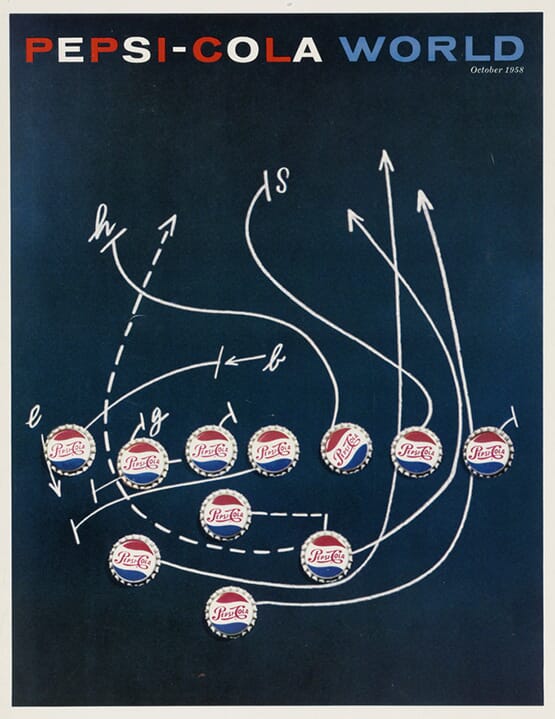

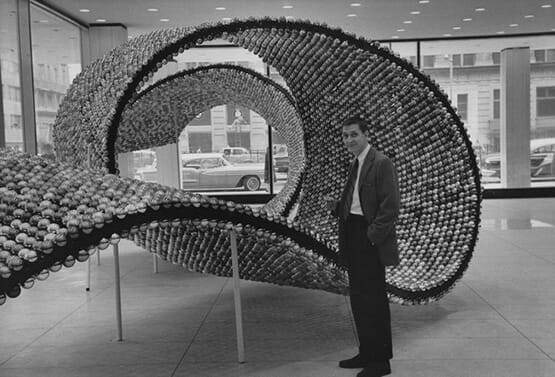

Until recently it took some serious graphic archaeology to unearth his work: type-spotters with back copies of Typographica would have seen his work as part of New York late-fifties hot-shop Brownjohn, Chermayeff and Geismar.

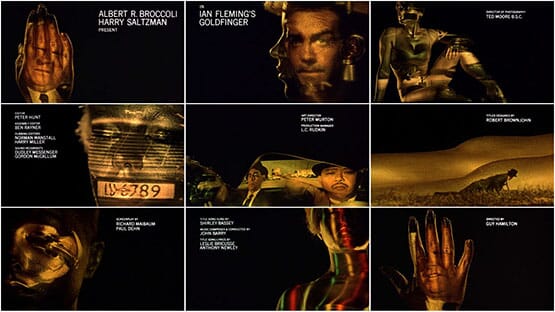

D&AD archivists would know his award-winning James Bond titles from the sixties where he projected type and images over a nubile young accomplice; Eye magazine dedicated a chunk of one of its early issues to him in the nineties.

Other than that, not a lot. So where does his influence stem from? Is it justified?

Absolutely. His name may not be well known but Brownjohn’s influence is everywhere. His reductionist approach still permeates through our graphic landscape fifty years later. His work still stands as fantastic antidote to whatever graphic trend we may all succumb to: nothing dates quicker than a style, nothing dates slower than a great idea. We have to credit Brownjohn for some of that.

Whether it’s his typographic skills on film, or his wanderings through London photographing ‘found’ street signage (seen every summer at degree shows around the country) he’s still here.

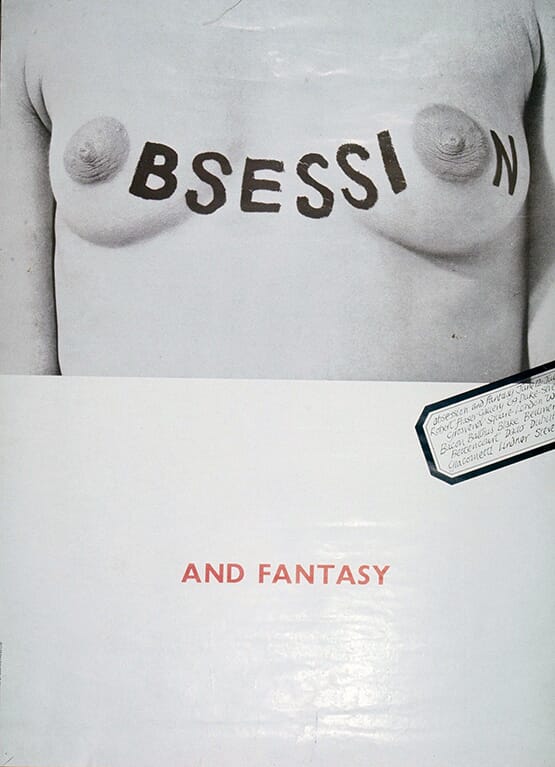

You can draw a direct line from his ‘Obsession’ poster to Stefan Sagmeister’s famously self-sacrificing AIGA poster.

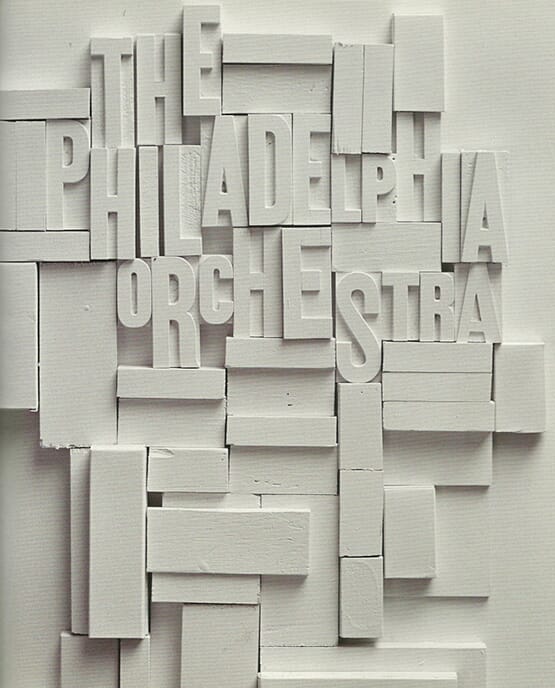

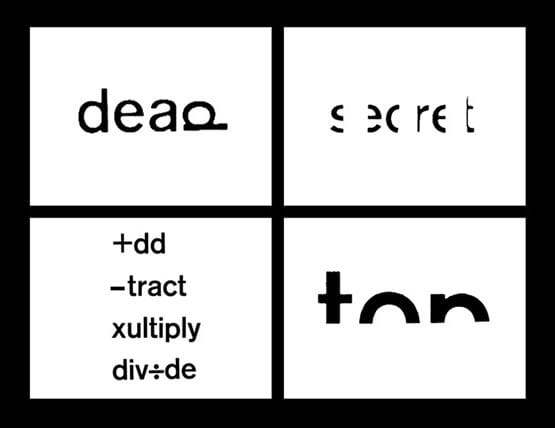

The ‘making words work’ letterplay continues to resonate today, most notably in Harry Pearce’s typographic experiments.

His ‘Peace’ poster with an ace of spades substituted for three of the letters is a sublime sleight of hand most of us would die to have in our portfolios.

Was his success all a question of good timing? Much has been made of his 60s arrival in London with Bob Gill, just as the decade began to swing - his approach to life certainly seemed to suit that decade’s decadence. But his serious extra-curricular habits didn’t stop him art directing ads and seminal posters whilst producing film titles, designing for the Rolling Stones (the back cover of Let it bleed is at the top of this post) in between popping out to catch Jimi Hendrix whilst featuring in a couple of films himself.

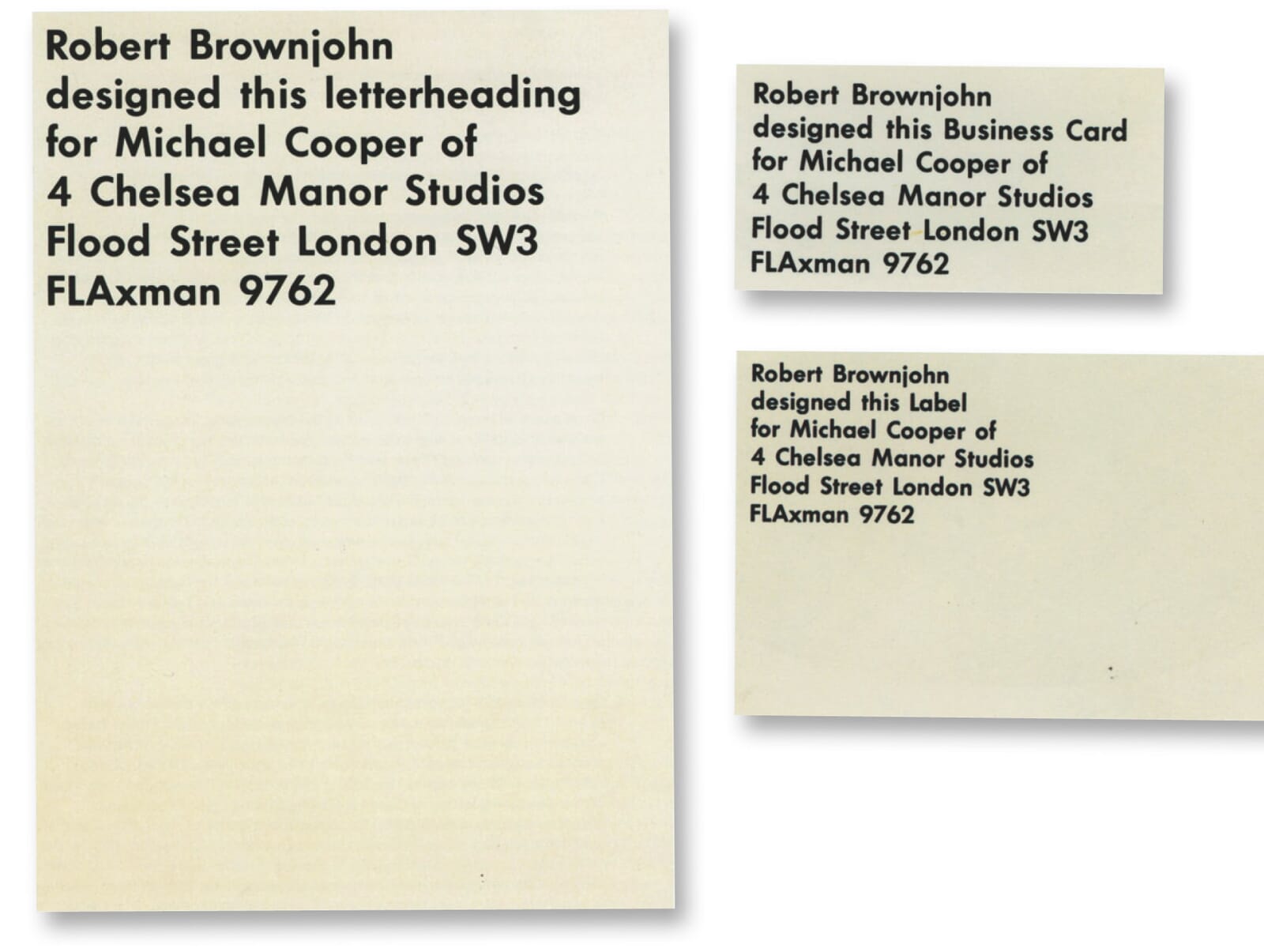

His 2,000 slide lectures of ‘unused ideas’ left a generation of designers permanently scarred. He was so well known by 1967 that when asked to design some stationery for Michael Cooper (photographer of the Sergeant Pepper sleeve) he simply typeset ‘Robert Brownjohn designed this letterheading for Michael Cooper’. You’ve got to be pretty sure of your genius to do that.

Perhaps where Brownjohn is concerned, some of the mystique stems from his death. Just as the Hendrix/Cobain/Drake/Buckley brand of genius is concentrated in a quick burst of brilliance crammed into a short space of time, Brownjohn’s output isn’t huge, but it’s all great. There was no time for a ‘quiet spell’ or a period spent vaguely art directing vast identities within a global branding concern, as might happen now. The brilliance has never been diluted by sub-standard fare and we’ve never had the chance to mutter those damning words ‘of course his early work was so much better’.

If you ever wanted a good ‘BJ’ story the first point of call was always his friend (the now deceased) Alan Fletcher so it’s especially apt that Fletcher designed Brownjohn’s retrospective. Quite a posthumous honour when you think about it, to have Mr Fletcher design your retrospective, but it’s indicative of just how highly Brownjohn is regarded. Thank you, BJ.

This article, written by Michael Johnson to preview the Design Museum’s show on Robert Brownjohn, was originally published in 2005.

Follow johnson banks on twitter @johnsonbanks, on Facebook or sign-up for our newsletter here